by Carolyn Clare Givens

Polonius: What do you read, my lord?

Hamlet: Words, words, words.

Hamlet, Act II, Scene II

I found my favorite word one day in college when my friend and I were reading through the dictionary together.

I say “reading,” but if you’re of the right age to remember paper dictionaries, you know that dictionary reading is an entirely different sport than reading a book of another kind. Reading the dictionary was a hunt-and-peck activity in which you’d open to a page (by choice or at random) and see what stood out to you. Or, if you were looking for a particular word, you sought that word but, along the way, discovered all sorts of delightful surprises, like “prestidigitation” on your way to “presumptuous.”

I’m not sure which version of the pastime Bekka and I were participating in that day. It’s entirely possible that we were looking up “hogback” or “hoary” when we encountered what may just be the best word in the English language: “hobbledehoy.”

Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 10th ed., defines “hobbledehoy” as “an awkward gawky youth.” As young ladies in college, surrounded by young men of such a description, “hobbledehoy” was a beacon for us—there was a WORD for them, and it was awfully fun to say.

I have come across the term “in the wild” just a few times. More often, it is used as a fun or difficult word, such as in this episode (my favorite!) of

when David and Graeme and Daniel Nayeri attempt to figure out the definition. But my dreams came true just a few years after my initial discovery of the word when I encountered it used with real, honest-to-goodness earnestness in Elizabeth Gaskell’s Wives and Daughters. In fact, this use was not simply a straight-up repetition of the dictionary use—no, Gaskell took the original and improved upon it.Her heroine, Molly, is a teenager when she first meets Roger, the son of her dear friends, the Squire and Mrs. Hamley. Roger is home from Cambridge, and his introduction is thus: “He certainly did not seem to care much what impression he made upon his mother's visitor. He was at that age when young men admire a formed beauty more than a face with any amount of future capability of loveliness, and when they are morbidly conscious of the difficulty of finding subjects of conversation in talking to girls in a state of feminine hobbledehoyhood.”

Glory be.

“A state of feminine hobbledehoyhood.”

Is there a better phrase to be had in all the language? I challenge Shakespeare to rival it.

“Hobbledehoy” remains to this day my favorite word to try to teach to children in the parrot stage of language acquisition, and my friend’s son used to say, “Hi-hoy” when I asked him to say it after me. It was adorable.

Words have long been my favorite things. Grammar is interesting, and stories are lovely, but the very building blocks of our language are what I love playing with. Modern English’s roots pull nutrients from Old Germanic languages, Old Norse, Norman French, and more, and the result is a fascinating hodge-podge of words that range from the mundane to the highfalutin.

In Mel Gibson’s Hamlet, when Polonius asks what he’s reading, Gibson responds with a different emphasis on each: the first “words” is questioning, as he looks at a book as if he’s discovering what’s in there; the second is confirmational in tone, as he flips through more pages; the third is his answer to Polonius, a hand gesture expressing the obvious statement, “Words.” (Sidenote: if you’ve never read Hamlet looking for the humor in it, do so again. It’s hilarious.)

When I taught college freshman writing skills, I challenged them to find three new vocabulary words each week—the catch being that they couldn’t just go look up words they didn’t know. Their assignment was to listen and look for new words they encountered in everyday life—to pay attention to the words around them and then look them up. Every single week, something I said in class wound up in someone’s vocab list—probably because I read the dictionary for fun in college.

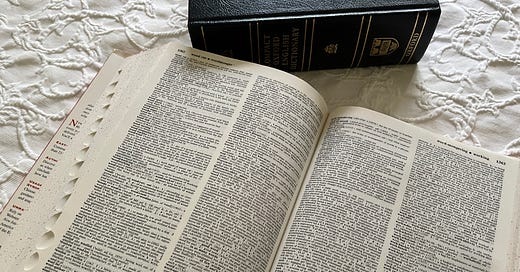

While I’m grateful to have the Merriam-Webster app on my phone and my Google search bar has the URL of the web version memorized, I regret that I don’t often pull out my 25-year-old 10th Edition of the Collegiate Dictionary (it was a high school graduation gift from my Uncle Marlin and Aunt Helen). The fun of a paper dictionary is not the speed at which you get your answer, but rather the joy of discovering delightful words along the way. On every page of a dictionary, there are 10s to 100s of words that are just waiting to be used.

So get yourselves a paper dictionary and keep it next to the Bible near the dinner table like my parents did. If a topic or a word came up that we didn’t understand, we asked, and often, Mom and Dad would reply, “Look it up.” Out came the Bible or the “Snollygoster” edition of a Merriam-Webster dictionary—so named because Dad once stumped all of us in a game of Probe with that word—and we discovered new worlds in the words on a page.

July 17–20: Sponsor Table at the CiRCE National Conference in Charleston, SC

Late July: Open submissions! More info to come.

August: Red Rex release (preorders open in late June)

November: Above, Not Up release (preorders open in September)

Carolyn Givens got to visit our friend Maile Silva at her new bookstore, Nooks, in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, last weekend. If you are anywhere near the area, head to Gallery Row in downtown Lancaster and check out Nooks—it’s a bookstore full of all the things we love (including a few Bandersnatch Books, too!).

Follow Bandersnatch Books on Instagram or Facebook!

I have an 1828 Websters dictionary that I made a swivel stand for (I tagged you in said Instagram post) and my favorite word is angiotensinogen.

My 10 year old has recently requested his own dictionary. I am going to have to find him a good one!